Written around 1000 AD by an unknown author, Beowulf is the first major work written in English at a time when the English identity was pretty non-existent. The story recounts the adventures of Beowulf, a Geatish prince from modern-day Sweden who slays three monsters throughout the book. Today we’ll talk about the second creature he kills: she’s a she-wolf, she’s a water witch, she’s Grendel’s mother.

Although she’s never given a name, Grendel’s mother is the subject of furious academic debate because nobody can decide what in the Heorot she is (IYKYK)! The first clue we get about her nature is around lines 106–114 where her son, the monster Grendel, is described as being descended from the biblical Cain, the first murderer, according to Abrahamic faiths. The poem mentions that whatever creatures who were born from Cain’s line were “ogres”, “elves”, “giants”, and “evil phantoms”, beings (except ogres and evil phantoms) that were considered benevolent in the previous pagan tradition (often granting boons or aiding individuals), but with the rise of the Christianity, turned malevolent (in an attempts to deter further worship). We can infer that Grendel’s mother is part of this lovely family tree.

But where we really get a good look at Grendel’s mother is when Beowulf goes to fight her. The poet claims she is an “aglæc-wif,” literally translating to “woman warrior,” however, translators seem to move away from the meaning and take on some strange descriptions instead. The first to provide such an interpretation is the German philologist, Fredrick Klaeber, who claims “aglæc-wif” means “wretch or monster woman”— a much more negative spin on “warrior woman”. This influenced other translators such as Seamus Heaney’s “monstrous hell-bride”, Charles Kennedy’s “monstrous hag”, and my personal favorite, Richard Trask’s “ugly troll lady”. These derogatory terms highlight her malevolence over warrior nature. Similar words are used in Aramaic incantations, where Lilith, credited with the birth of evil in the Judaic tradition, is called a “hell-hag,” “ghoul”, and the “mother of demons.”

In contrast, when Beowulf is also described as “aglæca,” translators interpret it as a reference to his superhuman and heroic strength. It adds to his duty of carrying out God’s work.

But when the two come to fight, it is Grendel’s mother who Beowulf struggles to vanquish— not Grendel himself who literally kidnapped the Danes from their beds, tore them apart, and ate them. If we compare their battle scene, things start getting a bit more strange.

Depiction of either Lilith or Ishtar; Burney Relief, Babylon (1800–1750 BC)

Grendel, who is decidedly a monster, possesses “claws”, a massive build, “glowing eyes”, and the ability to blunt weapons. When fighting him, Beowulf doesn’t decide to use any sort of weapon, but rather fights with his bare hands for honor and ends up tearing Grendel’s arm clean off, consequently killing him. Once Grendel sees the hero’s immense strength, his “one thought [is] to run from Beowulf” and to “hide” from him in his marsh.

The fight ends with Grendel fleeing and Beowulf being praised by the poet as “the strongest” of all “the men on earth.” It’s almost like Beowulf didn’t even break a sweat against the so-called “shepherd of evil”! But it’s not all his work as references to divine support are given by the Almighty, thus symbolizing the retreat of paganism from the superior Christianity.

In contrast, when Beowulf learns that he must combat Grendel’s mother, he puts on every piece of armor available and supplies himself with an allegedly infallible weapon called Hrunting. As she reveals herself, Grendel’s mother is called an “ides”, which roughly translates to “lady”, but is most commonly used in Old Germanic languages when referring to the Valkyries (female fighters who serve the supreme god Odin in Norse mythology), further establishing her role as a “warrior woman”. The word can also imply that she’s beautiful, but other than that, we don’t get much about her physical appearance. As Beowulf enters her domain beneath the water, the poet portrays her as a “fierce mother” who “welcome[s] [Beowulf] in her claws” and “works her fingers” through his armor.

She seduces Beowulf by feigning hospitality while trying to open his armor, symbolizing how she might seek to take off his emotional armor as a mother would do so for her child. It’s much softer than the tendon-ripping-and-screaming-filled scene with Grendel. The association with the stripping of one’s clothes with intimacy adds another layer to her enchantment. Similarly, Pandora from Greek mythology who unleashed all of the evils of the world by opening a jar, is described in Hesiod’s Theogony as possessing “sheer guile” and a “deceitful nature,” emphasizing her role in seduction. These descriptions generally assume a menacing intention, but Grendel’s mother seems to display at least a bit more empathy than any other creature Beowulf fights.

That being said, during their battle, she showcases unnatural strength by pinning Beowulf beneath her and creating an immunity against his supposedly legendry sword, Hrunting, all while surviving under water. Beowulf, “the best and strongest of soldiers” becomes “weary”, possibly for the first time in his violent career, and realizes that he is equally matched. He even at one point considers that his mortality is at risk as he is “held helpless” by her, a fearful thought that did not enter his mind when fighting Grendel.

The poet, however, notes some thing interesting here— that Grendel’s mother is “avenging her only son”. In Old English, “wergild” is the concept of vengeance or paying the price for a loved one, and is a common motif in Anglo-Saxon culture, even seen as a value to be praised. So why does Grendel’s mother, a supposed antagonist, display notable Anglo-Saxon virtues such as wergild, physical strength, and bravery?

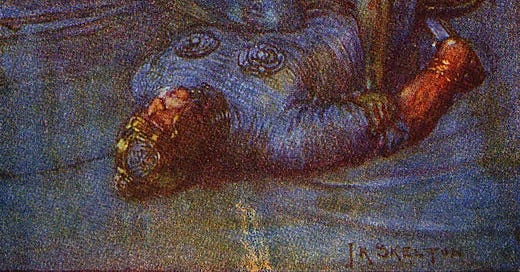

Illustration by J.R. Skelton from Stories of Beowulf (1908)

After what seems to be a sort of prayer to the Christian God, Beowulf becomes victorious, but only with the aid of a sword that hung in the hallway of Grendel’s mother’s realm. The text mentions that it was “hammered by giants” which is pretty ironic considering that the only tool that helped fulfill the Christian’s glory was a pagan one.

Although, after stabbing her in the neck, a “brilliant light” as bright as “Heaven’s own candle” is cast upon him, a symbol of the Almighty praising his power. Beowulf, however, does not accept it immediately. His “heart is still angry”, so he turns away from the light, dives further into the realm, takes up his sword and cuts Grendel’s head off from where it lay near his mother’s.

The tone here is very vicious, almost as if it were from the first-person point of view of Beowulf. If you look up that specific part where Beowulf hacks off the head, it seems like it would be read through clenched teeth. Up until now, Beowulf was firmly on the side of good, but now he enters a stage of moral ambiguity as it is only assumed he followed the light after the beheading, but it is never explicitly stated. The fact that he turned away from the Christian God in that moment should ring some alarm bells.

In the end, though, Beowulf is remembered as the hero completing his journey and bringing peace to his people. Grendel and his mother on the other hand, are a bit more antagonistically complex.

Grendel, in later and modern media, is always some sort of ogre or monstrous being while Grendel’s mother’s appearance varies from retelling to retelling. Sometimes she’s a sea witch, sometimes she’s a misunderstood human woman outcasted from society, or sometimes she’s a seductress played by a former Playboy model (1999) or Angelina Jolie (2007).

We still don’t know what she is. Who she is. With all this mention and association with paganism, I think it’s also fair to say that whatever she was before the codification of Beowulf and the spread of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon lands was possibly more ancient than the protagonist, Beowulf, himself. Maybe she was a goddess or, at least, a prominent figure in Proto-Germanic mythology. We can only read and admire and imagine what she could have been to the pagan peoples before.

Whatever she is, one thing is for certain: despite her villainy, without Grendel’s mother and her child, there would be no story of Beowulf’s heroism or, arguably, the Abrahamic God’s glory, just as without Eve mothering Original Sin, there would be no salvation for Jesus to give. The heroes of our treasured legends cannot complete their journeys without these “mothers of monsters” which we see throughout the mythological tapestry of the world, from Eve to Lilith to Pandora and back to Grendel’s mother…

Thanks for reading!

Keep telling and collecting stories,

Ava

Beowulf has always been fascinating, not for the tired prattle of conquering christianity, but for the ancient world that still shines out around abrahamic attempts to bind it to their political reality.

I am reminded it was always Aegir AND Ran, and that Balder's funerary ship had to be towed out by Giantesses.

There is the ancient creation story of Night, and the image that in sacred geometry the reflection of the ineffable is always the Mother of reality.

Ten worlds

In the Wood.

The image of a spiritual power removing armor is found across the spectrum of the lore.

The ancestors saw a great power in the nature of begetting. That such is a feminine power was never lost on them.